How do you make a sequel to a game that covers all of human history?

— Brian Reynolds

At the risk of making a niche website still more niche, allow me to wax philosophical for a moment on the subject of those Roman numerals that have been appearing just after the names of so many digital games almost from the very beginning. It seems to me that game sequels can be divided into two broad categories: the fiction-driven and the systems-driven.

Like so much else during gaming’s formative years, fiction-driven sequels were built off the example of Hollywood, which had already discovered that no happily ever after need ever be permanent if there was more money to be made by getting the old gang of heroes back together and confronting them with some new threat. Game sequels likewise promised their players a continuation of an existing story, or a new one that took place in a familiar setting with familiar characters. Some of the most iconic names in 1980s and early 1990s gaming operated in this mode: Zork, Ultima, Wizardry, King’s Quest, Carmen Sandiego, Leisure Suit Larry, Wing Commander. As anyone who has observed the progress of those series will readily attest, their technology did advance dramatically over the years. And yet this was only a part of the reason people stayed loyal to them. Gamers also wanted to get the next bit of story out of them, wanted to do something new in their comfortingly recognizable worlds. Unsurprisingly, the fiction-driven sequel was most dominant among games that foregrounded their fictions — namely the narrative-heavy genres of the adventure game and the CRPG.

But there was another type of sequel, which functioned less like a blockbuster Hollywood franchise and more like the version numbers found at the end of other types of computer software. It was the domain of games that were less interested in their fictions. These sequels rather promised to do and be essentially the same thing as their forerunner(s), only to do and be it even better, taking full advantage of the latest advances in hardware. Throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s, the technology- or systems-driven sequel was largely confined to the field of vehicular simulations, a seemingly fussily specific pursuit that was actually the source in some years of no less than 25 percent of the industry’s total revenues. The poster child for the category is Microsoft’s Flight Simulator series, the most venerable in the entire history of computer gaming, being still alive and well as I write these words today, almost 43 years after it debuted on the 16 K Radio Shack TRS-80 under the imprint of its original publisher subLogic. If you were to follow this franchise’s evolution through each and every installment, from that monochrome, character-graphic-based first specimen to today’s photo-realistic feast for the senses, you’d wind up with a pretty good appreciation of the extraordinary advances personal computing has undergone over the past four decades and change. Each new Flight Simulator didn’t so much promise a new experience as the same old one perfected, with better graphics, better sound, a better frame rate, better flight modeling, etc. When you bought the latest Flight Simulator — or F-15 Strike Eagle, or Gunship, or Falcon — you did so hoping it would take you one or two steps closer to that Platonic ideal of flying the real thing. (The fact that each installment was so clearly merely a step down that road arguably explains why these types of games have tended to age more poorly than others, and why you don’t find nearly as many bloggers and YouTubers rhapsodizing about old simulations today as you do games in most other genres.)

For a long time, the conventional wisdom in the industry held that strategy games were a poor fit with both of these modes of sequel-making. After all, they didn’t foreground narrative in the same way as adventures and CRPGs, but neither were they so forthrightly tech-centric as simulations. As a result, strategy games — even the really successful ones — were almost always standalone affairs.

But all that changed in a big way in 1993, when Maxis Software released SimCity 2000, a sequel to its landmark city-builder of four years earlier. SimCity 2000 was a systems-driven sequel in the purest sense. It didn’t attempt to be anything other than what its predecessor had been; it just tried to be a better incarnation of that thing. Designer Will Wright had done his level best to incorporate every bit of feedback he had received from players of his original game, whilst also taking full advantage of the latest hardware to improve the graphics, sound, and interface. “Is SimCity 2000 a better program than the original SimCity?” asked Computer Gaming World magazine rhetorically. “It is without question a superior program. Is it more fun than the original SimCity? It is.” Wright was rewarded for his willingness to revisit his past with another huge hit, even bigger than his last one.

Other publishers greeted SimCity 2000‘s success as something of a revelation. At a stroke, they realized that the would-be city planners and generals among their customers were as willing as the would-be pilots and submarine captains to buy a sequel that enhanced a game they had already bought before, by sprucing up the graphics, addressing exploits, incongruities, and other weaknesses, and giving them some additional complexity to sink their teeth into. For better or for worse, the industry’s mania for franchises and sequels thus came to encompass strategy games as well.

In the next few articles, I’d like to examine a few of the more interesting results of this revelation — not SimCity 2000, a game about which I have oddly little to say, but another trio that would probably never have come to be without it to serve as a commercial proof of concept. All of the games I’ll write about are widely regarded as strategy classics, but I must confess that I can find unreserved love in my heart for only one of them. As for which one that is, and the reasons for my slight skepticism about the others… well, you’ll just have to read on and see, won’t you?

Civilization, Sid Meier’s colossally ambitious and yet compulsively playable strategy game of everything, was first released by MicroProse Software just in time to miss the bulk of the Christmas 1991 buying season. That would have been the death knell of many a game, but not this one. Instead Civilization became the most celebrated computer game since SimCity in terms of mainstream-media coverage, even as it also became a great favorite with the hardcore gamers. Journalists writing for newspapers and glossy lifestyle magazines were intrigued by it for much the same reason they had been attracted to SimCity, because its sweeping, optimistic view of human Progress writ large down through the ages marked it in their eyes as something uniquely high-toned, inspiring, and even educational in a cultural ghetto whose abiding interest in dwarfs, elves, and magic spells left outsiders like them and their readers nonplussed. The gamers loved it, of course, simply because it could be so ridiculously fun to play. Never a chart-topping hit, Civilization became a much rarer and more precious treasure: a perennial strong seller over months and then years, until long after it had begun to look downright crude in comparison to all of the slick multimedia extravaganzas surrounding it on store shelves. It eventually sold 850,000 copies in this low-key way.

Yet neither MicroProse nor Sid Meier himself did anything to capitalize on its success for some years. The former turned to other games inside and outside of the grand-strategy tent, while the latter turned his attention to C.P.U. Bach, a quirky passion project in computer-generated music that wasn’t even a game at all and didn’t even run on conventional computers. (Its home was the 3DO multimedia console.) The closest thing to a Civilization sequel or expansion in the three years after the original game’s release was Colonization, a MicroProse game from designer Brian Reynolds that borrowed some of Civilization‘s systems and applied them to the more historically grounded scenario of the European colonization of the New World. The Colonization box sported a blurb declaring that “the tradition of Civilization continues,” while Sid Meier’s name became a possessive prefix before the new game’s title. (Reynolds’s own name, by contrast, was nowhere to be found on the box.) Both of these were signs that MicroProse’s restless marketing department felt that the legacy of Civilization ought to be worth something, even if it wasn’t yet sure how best to make use of it.

Colonization hit the scene in 1994, one year after SimCity 2000 had been accorded such a positive reception, and proceeded to sell an impressive 300,000 copies. These two success stories together altered MicroProse’s perception of Civilization forever, transforming what had started as just an opportunistic bit of marketing on Colonization‘s box into an earnest attempt to build a franchise. Not one but two new Civilization games were quickly authorized. The one called CivNet was rather a stopgap project, which transplanted the original game from MS-DOS to Windows and added networked or hot-seat multiplayer capabilities to the equation. The other Civilization project was also to run under Windows, but was to be a far more extensive revamping of the original, making it bigger, prettier, and better balanced than before. Its working title of Civilization 2000 made clear its inspiration. Only at the last minute would MicroProse think better of making SimCity 2000‘s influence quite so explicit, and rename it simply Civilization II.

Unfortunately for MicroProse’s peace of mind, Sid Meier, a designer who always followed his own muse, said that he had no interest whatsoever in repeating himself at this point in time. Thus the project devolved to Brian Reynolds as the logical second choice: he had acquitted himself pretty well with Colonization, and Meier liked him a lot and would at least be willing to serve as his advisor, as he had for Reynold’s first strategy game. “They pitched it to me as if [they thought] I was probably going to be really upset,” laughs Reynolds. “I guess they thought I had my heart set on inventing another weird idea like Colonization. ‘Okay, will he be too mad if we tell him that we want him to do Civilization 2000?’ Which of course to me was the ultimate dream job. You couldn’t have asked me to do something I wanted to do more than make a version of Civilization.”

Like his mentor Meier, Reynolds was an accomplished programmer as well as game designer. This allowed him to do the initial work of hammering out a prototype on his own — from, of all locations, Yorkshire, England, where he had moved to be with his wife, an academic who was there on a one-year Fullbright scholarship. While she went off to teach and be taught every day, he sat in their little flat putting together the game that would transform Civilization from a one-off success into the archetypal strategy franchise.

Brian Reynolds

As Reynolds would be the first to admit, Civilization II is more of a nuts-and-bolts iteration on what came before than any wild flight of fresh creativity. He approached his task as a sacred trust. Reynolds:

My core vision for Civ II was not to be the guy that broke Civilization. How can I make each thing a little bit better without breaking any of it? I wanted to make the AI better. I wanted to make it harder. I wanted to add detail. I wanted to pee in all the corners. I didn’t have the idea that we were going to change one thing and everything else would stay the same. I wanted to make everything a little bit better. So, I both totally respected [Civilization I] as an amazing game, and thought, I can totally do a better job at every part of this game. It was a strange combination of humility and arrogance.

Reynolds knew all too well that Civilization I could get pretty wonky pretty quickly when you drilled down into the details. He made it his mission to fix as many of these incongruities as possible — both the ones that could be actively exploited by clever players and the ones that were just kind of weird to think about.

At the top of his list was the game’s combat system, the source of much hilarity over the years, what with the way it made it possible — not exactly likely, mind you, but possible — for a militia of ancient spearmen to attack and wipe out a modern tank platoon. This was a result of the game’s simplistic “one hit and done” approach to combat. Let’s consider our case of a militia attacking tanks. A militia has an attack strength of one, a tank platoon a defense strength of five. The outcome of the confrontation is determined by adding these numbers together, then taking each individual unit’s strength as its chance of destroying the other unit rather than being destroyed itself. In this case, then, our doughty militia men have a one-in-six chance of annihilating the tanks rather than vice versa — not great odds, to be sure, but undoubtedly better than those they would enjoy in any real showdown.

It was economic factors that made this state of affairs truly unbalancing. A very viable strategy for winning Civilization every single time was the “barbarian hordes” approach: forgo virtually all technological and social development, flood the map with small, primitive cities, then use those cities to pump out huge numbers of primitive units. A computer opponent diligently climbing the tech tree and developing its society over a broader front would in time be able to create vastly superior units like tanks, but would never come close to matching your armies in quantity. So, you could play the law of averages: you might have to attack a given tank platoon five times or more with different militias, but you knew that you would eventually destroy it, as you would the rest of your opponent’s fancy high-tech military with your staggering numbers of bottom feeders. The barbarian-horde strategy made for an unfun way to play once the joy of that initial eureka moment of discovering it faded, yet many players found the allure of near-certain victory on even the highest difficulty levels hard to resist. Part of a game designer’s job is to save players like this from themselves.

This was in fact the one area of Civilization II that Sid Meier himself dived into with some enthusiasm. He’d been playing a lot of Master of Magic, yet another MicroProse game that betrayed an undeniable Civilization influence, although unlike Colonization it was never marketed on the basis of those similarities. When two units met on the world map in Master of Magic, a separate tactical-battle screen opened up for you to manage the fight. Meier went so far as prototyping such a system for Civilization II, but gave up on it in the end as a poor fit with the game’s core identity. “Being king is the heart of Civilization,” he says. “Slumming as a lowly general puts the player in an entirely different story (not to mention violates the Covert Action rule). Win-or-lose battles are not the only interesting choice on the path to good game design, but they’re the only choice that leads to Civ.”

With his mentor having thus come up empty, Brian Reynolds addressed the problem via a more circumspect complication of the first game’s battle mechanics. He added a third and fourth statistic to each unit: firepower and hit points. Now, instead of being one-and-done, each successful “hit” would merely subtract the one unit’s firepower from the other’s total hit points, and then the battle would continue until one or the other reached zero hits points. The surviving unit would quite possibly exit the battle “wounded” and would need some time to recuperate, adding another dimension to military strategy. It was still just barely possible that a wildly inferior unit could defeat its better — especially if the latter came into a battle already at less than its maximum hit points — but such occurrences became the vanishingly rare miracles they ought to be. Consider: Civilization II‘s equivalent of a militia — renamed now to “warriors” — has ones across the board for all four statistics; a tank platoon, by contrast, has an attack strength of ten, a defense strength of five, a firepower of one, and three hit points when undamaged. This means that a group of ancient warriors needs to roll the same lucky number three times in a row on a simulated six-sided die in order to attack an undamaged tank platoon and win. A one-in-six chance has become one chance in 216 — odds that we can just about imagine applying in the real world, where freak happenstances really do occur from time to time.

This change was of a piece with those Reynolds introduced at every level of the game — pragmatic and judicious, evolutionary rather than revolutionary in spirit. I won’t enumerate them exhaustively here, but will just note that they were all very defensible if not always essential in this author’s opinion.

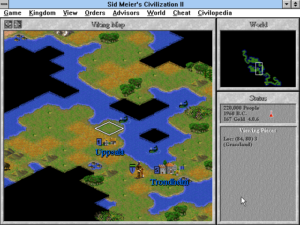

Civilization II was written for Windows 3, and uses that operating system’s standard Windows interface.

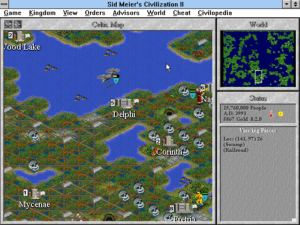

The layers of the program that were not immediately visible to the player got an equally judicious sprucing up — especially diplomacy and artificial intelligence, areas where the original had been particularly lacking. The computer players became less erratic in their interactions with you and with one another; no longer would Mahatma Gandhi go to bed one night a peacenik and wake up a nuke-spewing madman. Combined with other systemic changes, such as a rule making it impossible for players to park their military units inside the city boundaries of their alleged allies, these improvements made it much less frustrating to pursue a peaceful, diplomatic path to victory — made it less likely, that is to say, that the other players would annoy you into opening a can of Gandhi-style whip-ass on them just to get them out of your hair.

In addition to the complications that were introduced to address specific weaknesses of the first game, Civilization II got a whole lot more stuff for the sake of it: more nationalities to play and play against (21 instead of 14); more advances to research (89 instead of 71); more types of units to move around the map (51 instead of 28); a bewildering variety of new geological, biological, and ecological parameters to manipulate to ensure that the game built for you just the sort of random world that you desired to play in; even a new, ultra-hard “Deity” difficulty level to address Reynold’s complaint that Meier’s Civilization was just too easy. There was also a new style of government added to the original five: “Fundamentalism” continued the tradition of mixing political, economic, and now religious ideologies indiscriminately, with all of them seen through a late-twentieth-century American triumphalist lens that might have been offensive if it wasn’t so endearingly naïve in its conviction that the great debates down through history about how human society can be most justly organized had all been definitively resolved in favor of American-style democracy and capitalism. And then the game got seven new Wonders of the World to add to the existing 21. Like their returning stablemates, they were a peculiar mix of the abstract and the concrete, from Adam Smith’s Trading Company (there’s that triumphalism again!) in the realm of the former to the Eiffel Tower in that of the latter.

Reynolds’s most generous move of all was to crack open the black box of the game for its players, turning it into a toolkit that let them try their own hands at strategy-game design. Most of the text and vital statistics were stored in plain-text files that anyone could open up in an editor and tinker with. Names could be changed, graphics and sounds could be replaced, and almost every number in the game could be altered at will. MicroProse encouraged players to incorporate their most ambitious “mods” into set-piece scenarios, which replaced the usual randomized map and millennia-spanning timeline with a more focused premise. Scenarios dealing with Rome during the time of transition from Republic to Empire and World War II in Europe were included with the game to get the juices flowing. In shrinking the timeline so dramatically and focusing on smaller goals, scenarios did tend to bleed away some of Civilization‘s high-concept magic and turn it into more of a typical strategic war game, but that didn’t stop the hardcore fans from embracing them. They delivered scenarios of their own about everything from Egyptian, Greek, and Norse mythology to the recent Gulf War against Iraq, from a version of Conway’s Game of Life to a cut-throat competition among Santa’s elves to become the dominant toy makers.

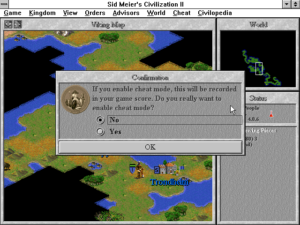

The ultimate expression of Brian Reynolds’s toolkit approach can be seen right there on the menu every time you start a new game of Civilization II, under the heading of simply “Cheat.” You can use it to change anything you want any time you want, at the expense of not having your high score recorded, should you earn one. At a click of the mouse, you can banish an opposing player from the game, research any advance instantly, give yourself infinite money… you name it. More importantly in the long run, the Cheat menu lets you peak behind the curtain to find out exactly what is going on at any given moment, almost like a programmer sitting in front of a debugging console. Sid Meier was shocked the first time he saw it.

Cheating was an inherent part of the game now, right on the main screen? This was not good. Like all storytelling, gaming is about the journey, and if you’re actively finding ways to jump to the end, then we haven’t made the fantasy compelling enough. A gripping novel would never start with an insert labeled, “Here’s the Last Page, in Case You Want to Read It Now.” Players who feel so inclined will instinctively find their own ways to cheat, and we shouldn’t have to help them out. I could not be convinced this was a good idea.

But Reynolds stuck to his guns, and finally Meier let him have it his way. It was, he now acknowledges, the right decision. The Cheat menu let players rummage around under the hood of the game as it was running, until some of them came to understand it practically as well as Reynolds himself. This was a whole new grade of catnip for the types of mind that tend to be attracted by big, complex strategy games like this one. Meanwhile the loss of a high score to boast about was enough to ensure that gamers weren’t unduly tempted to use the Cheat menu when playing for keeps, as it were.

Of course, the finished Civilization II is not solely a creation of Brian Reynolds. After he returned from Britain with his prototype in hand, two other MicroProse designers named Doug Kaufman and Jeff Briggs joined him for the hard work of polishing, refining, and balancing. Ditto a team of artists and even a film crew.

Yes, a film crew: the aspect of Civilization II that most indelibly dates it to the mid-1990s — even more so than its Windows 3 interface — must surely be your “High Council,” who pop up from time to time to offer their wildly divergent input on the subject of what you should be doing next. They’re played by real actors, hamming it up gleefully in video clips, changing from togas to armor to military uniforms to business suits as the centuries go by. Most bizarre of all is the entertainment advisor, played by… an Elvis Presley impersonator. What can one say? This sort of thing was widely expected to be the future of gaming, and MicroProse didn’t want to be left completely in the cold when the much-mooted merger of Silicon Valley and Hollywood finally became a reality.

Civilization II was released in the spring of 1996 to glowing reviews. Computer Gaming World gave it five stars out of five, calling it “a spectacularly addictive and time-consuming sequel.” Everything I’ve said in this article and earlier ones about the appeal, success, and staying power of Civilization I applies treble to Civilization II. It sold 3 million copies over the five years after its release, staying on store shelves right up to the time that the inevitable Civilization III arrived to replace it. Having now thoroughly internalized the lesson that strategy games could become franchises too, MicroProse sustained interest in the interim with two scenario packs, a “Multiplayer Gold Edition” that did for Civilization II what CivNet had done for Civilization I, and another reworking called Civilization II: Test of Time that extended the timeline of the game into the distant future. Civilization as a whole thus become one of gaming’s most inescapable franchises, the one name in the field of grand strategy that even most non-gamers know.

Given all of this, and given the obvious amount of care and even love that was lavished on Civilization II, I feel a bit guilty to admit that I struggled to get into it when I played it in preparation for this article. Some of my lack of enthusiasm may be down to purely proximate causes. I played a lot of Civilization I in preparation for the long series of articles I wrote about it and the Progress-focused, deeply American worldview it embodies, and the sequel is just more of the same from this perspective. If I’d come to Civilization II cold, as did the majority of those 3 million people who bought it, I might well have had a very different experience with it.

Still, I do think there’s a bit more to my sense of vague dissatisfaction than just a jaded player’s ennui. I miss one or two bold leaps in Civilization II to go along with all of the incrementalist tinkering. Its designers made no real effort to address the big issues that dog games of this ilk: the predictable tech tree that lends itself to rote strategies, the ever more crushing burden of micromanagement as your empire expands, and an anticlimactic endgame that can go on for hours after you already know you’re going to win. How funny to think that Master of Orion, another game published by MicroProse, had already done a very credible job of addressing all of these problems three years before Civilization II came to be!

Then, too, Civilization II may be less wonky than its predecessor, but I find that I actually miss the older game’s cock-eyed jeu d’esprit, of which those ancient militias beating up on tanks was part and parcel. Civilization II‘s presentation, using the stock Windows 3 menus and widgets, is crisper and cleaner, but only adds to the slight sense of sterility that dogs the whole production. Playing it can feel rather like working a spreadsheet at times — always a danger in these kinds of big, data-driven strategy games. Those cheesy High Council videos serve as a welcome relief from the austerity of it all; if you ask me, the game could have used some more of that sort of thing.

I do appreciate the effort that went into all the new nationalities, advances, units, and starting parameters. In the end, though, Civilization II only provides further proof for me — as if I needed it — that shoehorning more stuff into a game doesn’t always or even usually make it better, just slower and more ponderous. In this sense too, I prefer its faster playing, more lovably gonzo predecessor. It strikes me that Civilization II is more of a gamer’s game, emphasizing min-maxing and efficient play above all else, at the expense of the original’s desire to become a flight of the imagination, letting you literally write your own history of a world. Sid Meier liked to call his game first and foremost “an epic story.” I haven’t heard any similar choice of words from Brian Reynolds, and I’ve definitely never felt when playing Civilization I that it needed to be harder, as he did.

I hasten to emphasize, however, that mine is very much a minority opinion. Civilization II was taken up as a veritable way of life by huge numbers of strategy gamers, some of whom have refused to abandon it to this day, delivering verdicts on the later installments in the series every bit as mixed as my opinions about this one. Good for them, I say; there are no rights or wrongs in matters like these, only preferences.

Postscript: The Eternal War

In 2012, a fan with the online handle of Lycerius struck a chord with media outlets all over the world when he went public with a single game of Civilization II which he had been playing on and off for ten years of real time. His description of it is… well, chilling may not be too strong a word.

The world is a hellish nightmare of suffering and devastation. There are three remaining super nations in AD 3991, each competing for the scant resources left on the planet after dozens of nuclear wars have rendered vast swaths of the world uninhabitable wastelands.

The ice caps have melted over 20 times, due primarily to the many nuclear wars. As a result, every inch of land in the world that isn’t a mountain is inundated swampland, useless to farming. Most of which is irradiated anyway.

As a result, big cities are a thing of the distant past. Roughly 90 percent of the world’s population has died either from nuclear annihilation or famine caused by the global warming that has left absolutely zero arable land to farm. Engineers are busy continuously building roads so that new armies can reach the front lines. Roads that are destroyed the very next turn. So, there isn’t any time to clear swamps or clean up the nuclear fallout.

Only three massive nations are left: the Celts (me), the Vikings, and the Americans. Between the three of us, we have conquered all the other nations that have ever existed and assimilated them into our respective empires.

You’ve heard of the 100 Year War? Try the 1700 Year War. The three remaining nations have been locked in an eternal death struggle for almost 2000 years. Peace seems to be impossible. Every time a ceasefire is signed, the Vikings will surprise-attack me or the Americans the very next turn, often with nuclear weapons. So, I can only assume that peace will come only when they’re wiped out. It is this that perpetuates the war ad infinitum.

Because of SDI, ICBMs are usually only used against armies outside of cities. Instead, cities are constantly attacked by spies who plant nuclear devices which then detonate. Usually the downside to this is that every nation in the world declares war on you. But this is already the case, so it’s no longer a deterrent to anyone, myself included.

The only governments left are two theocracies and myself, a communist state. I wanted to stay a democracy, but the Senate would always overrule me when I wanted to declare war before the Vikings did. This would delay my attack and render my turn and often my plans useless. And of course the Vikings would then break the ceasefire like clockwork the very next turn. I was forced to do away with democracy roughly a thousand years ago because it was endangering my empire. But of course the people hate me now, and every few years since then, there are massive guerrilla uprisings in the heart of my empire that I have to deal with, which saps resources from the war effort.

The military stalemate is airtight, perfectly balanced because all remaining nations already have all the technologies, so there is no advantage. And there are so many units at once on the map that you could lose twenty tank units and not have your lines dented because you have a constant stream moving to the front. This also means that cities are not only tiny towns full of starving people, but that you can never improve the city. “So you want a granary so you can eat? Sorry! I have to build another tank instead. Maybe next time.”

My goal for the next few years is to try to end the war and use the engineers to clear swamps and fallout so that farming may resume. I want to rebuild the world. But I’m not sure how.

One can’t help but think about George Orwell’s Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia when reading of Lycerius’s three perpetually warring empires. Like Nineteen Eighty-Four, his after-action report has the uncanny feel of a dispatch from one of our own world’s disturbingly possible futures. Many people today would surely say that recent events have made his dystopia seem even more probable than ten years ago.

But never fear: legions of fans downloaded the saved game of the “Eternal War” which Lycerius posted and started looking for a way to end the post-apocalyptic paralysis. A practical soul who called himself “stumpster” soon figured out how to do so: “I opted for a page out of MacArthur’s book and performed my own Incheon landing.” In the game of Civilization, there is always a way. Let us hope the same holds true in reality.

(Sources: the book Sid Meier’s Memoir! by Sid Meier; Computer Gaming World of April/May 1985, November 1987, March 1993, June 1996, July 1996, and August 1996; Retro Gamer 86, 112, and 219. Online sources include Soren Johnson’s interviews with Sid Meier and Brian Reynolds, PC Gamer‘s “Complete History of Civilization,” and Huffington Post‘s coverage of Lycerius’s game of Civilization and stumpster’s resolution of the stalemate. The original text of original Lycenrius’s Reddit message is posted on the Civilization II wiki.

Civilization II is not currently available for online purchase. You can, however, find it readily enough on any number of abandonware archives; some are dodgier than others, so be cautious. I recommend that you avoid the Multiplayer Gold Edition in favor of the original unless you really, really want to play with your mates. For, in a rather shocking oversight, MicroProse released the Gold Edition with bugged artificial intelligence that makes all of the computer-controlled players ridiculously aggressive and will keep you more or less constantly at war with everyone. If perpetual war is your thing, on the other hand, go for it…

Once you’ve managed to acquire it, there’s a surprisingly easy way to run Civilization II on modern versions of Windows. You just need to install a little tool called WineVDM, and then the game should install and run transparently, right from the Windows desktop. It’s probably possible to get it running on Linux and MacOS using the standard Wine layer, but I haven’t tested this personally.)

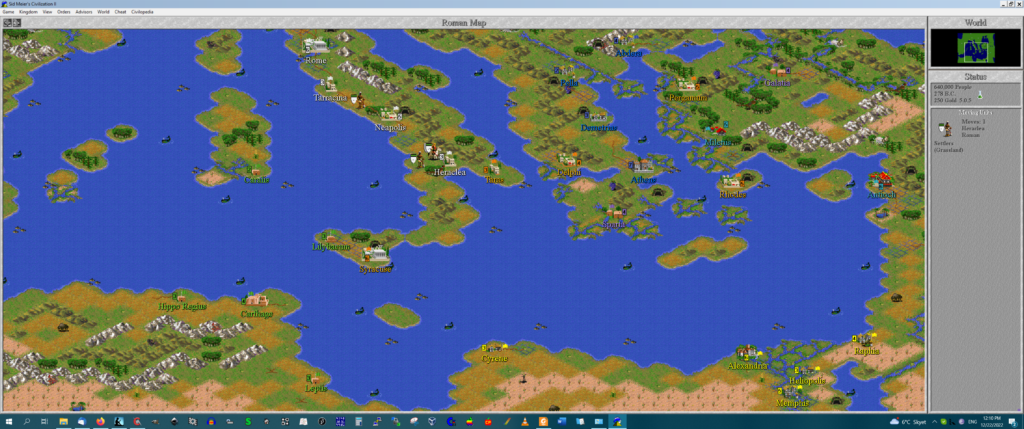

In a feat of robust programming of which its makers deserve to be proud, Civilization II is capable of scaling to seemingly any size of screen. Here it is running on my Windows 10 desktop at a resolution of 3440 X 1440 — numbers that might as well have been a billion by a million back in 1996.

Source link