Anne Weir was “quite shocked to see a rather large gate across the road and deer fencing stretching across the hill on either side” on a walk up Geal Charn Mhòr via the Burma Road and sent these photos to parkswatch along with a couple of comments.

Anne noted that that there was still lots of machinery on the hillside and “The signage doesn’t provide any information (for those who are interested) on the type of work, why it is necessary and how long it will take to complete.”

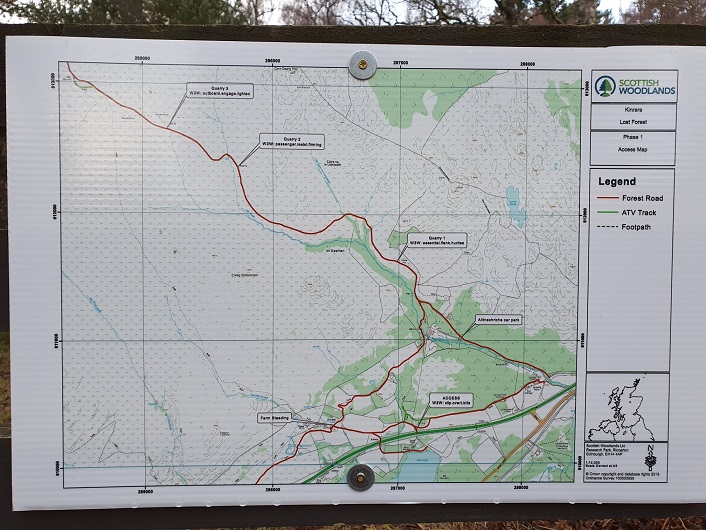

The Burma Road, a historic route enjoyed by many is now “A Forest Road” along with other tracks on BrewDog’s Kinrara estate. The main feature shown on the map is the location of quarries, though how these link to the creation of the Lost Forest is not explained.

Commentary

The Cairngorms National Park Authority National Park Partnership Plan 2022-27 aims to create 35,000 hectares of new woodland by 2045 which:

“Minimises the amount of fencing in the National Park by favouring establishment through herbivore management and removing redundant fences.”

Anne’s photos suggest the plan could hardly have made a worse start!

This fencing will have already directed yet more deer down the River Dulnain, contributing to the numbers seen there early in the New Year (see here) adding to the grazing pressure on Kinveachy where Seafield Estates are trying to enable the restoration of the Caledonian Forest by natural regeneration and without planting or fencing.

“Diverse, well-planned, climate-resilient and productive woodland will continue to generate economic and conservation benefits in the National Park. This plan sets out a direction for woodland that is about increasing areas of natural regeneration; however, planting and fencing will still be required in some places, notably those with limited seed sources and where there is conflict with herbivore impacts (especially in the early years of the plan).” (CNPA NPPP)

There are large amounts of seed at Kinrara, so all that is required for this hillside to regenerate naturally is to reduce the grazing pressure further but BrewDog has produced no plan to do that.

“Fencing is recognised as an important tool for woodland management but it can have negative impacts. Its use should be carefully considered and, before fencing is agreed, establishment through herbivore management should be encouraged where the surrounding land use context is favourable”

So who considered the landscape impact of this fencing before Scottish Forestry agreed to fork out over £1m in public monies to pay for it and the planting? And what herbivore management did BrewDog undertake BEFORE deciding the fences were needed?

Dave Morris will consider land-management at Kinrara further in another post but meantime it is worth taking a look at the finances.

How much is BrewDog investing at Kinrara?

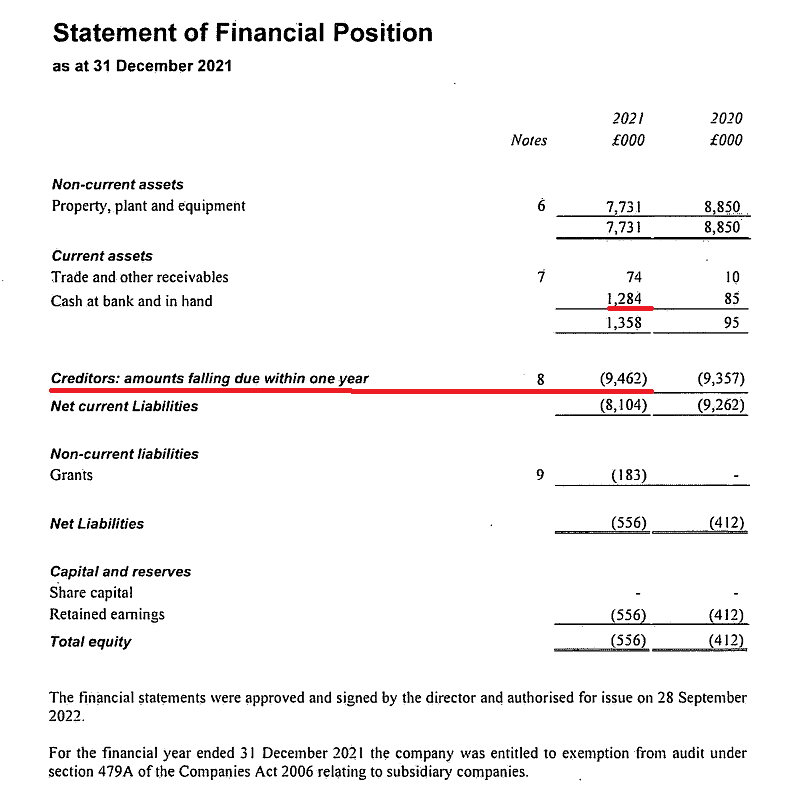

BrewDog owns and manages Kinrara through a fully owned subsidiary, the Lost Forest Ltd, which has published accounts for the years 2020 and 2021 (see here). Prior to that it was a dormant company known as BrewDog Admin Ltd.

There is also information about the Lost Forest in the main accounts for BrewDog PLC (see here) which are presented with their usual punk bravado and panache

BrewDog may be “defiant” but that is not necessarily a helpful quality when it comes to managing land wisely and their accounts raise serious questions about how much they are really investing at Kinrara.

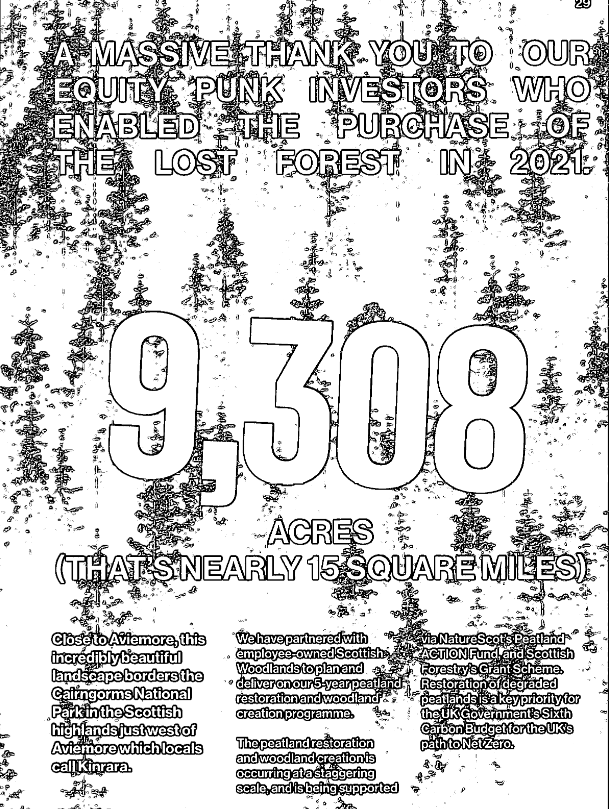

BrewDog’s main accounts till 2021 contain a thank you to their “equity punk investors” and those for the previous year reported they had raised over £25m to fund the purchase Kinrara and other green projects:

Note the acknowledgement that the actual restoration work at Kinrara is being supported by the Peatland Action Fund and the Scottish Forestry Grant Scheme.

What is not stated in the accounts is how much money BrewDog has invested itself in this work so far, only that in the year till December 2020 (note 6) the Lost Forest Ltd received £183k from Peatland Action.

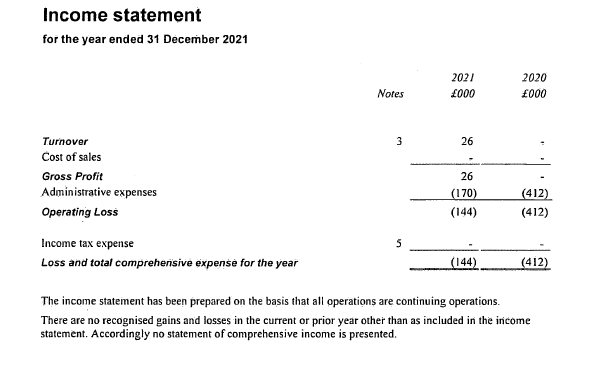

The income statement for the Lost Forest in 2021 shows very little activity and appears to support the claims made in the Guardian article last March (see here) that BrewDog was not investing what it had claimed at Kinrara:

“Early promotions for the Lost Forest suggested each can or pack of Lost Lager sold would fund a tree at Kinrara.

The money raised by investors to buy Kinrara is shown by the accounts as owing to BrewDog

It is difficult to understand WHY the overall debt of the company would be increasing, even if only slightly, if BrewDog was making a real investment in running the property. But the net effect of the debt is that the Lost Forest has negative equity, i.e. is effectively bankrupt:

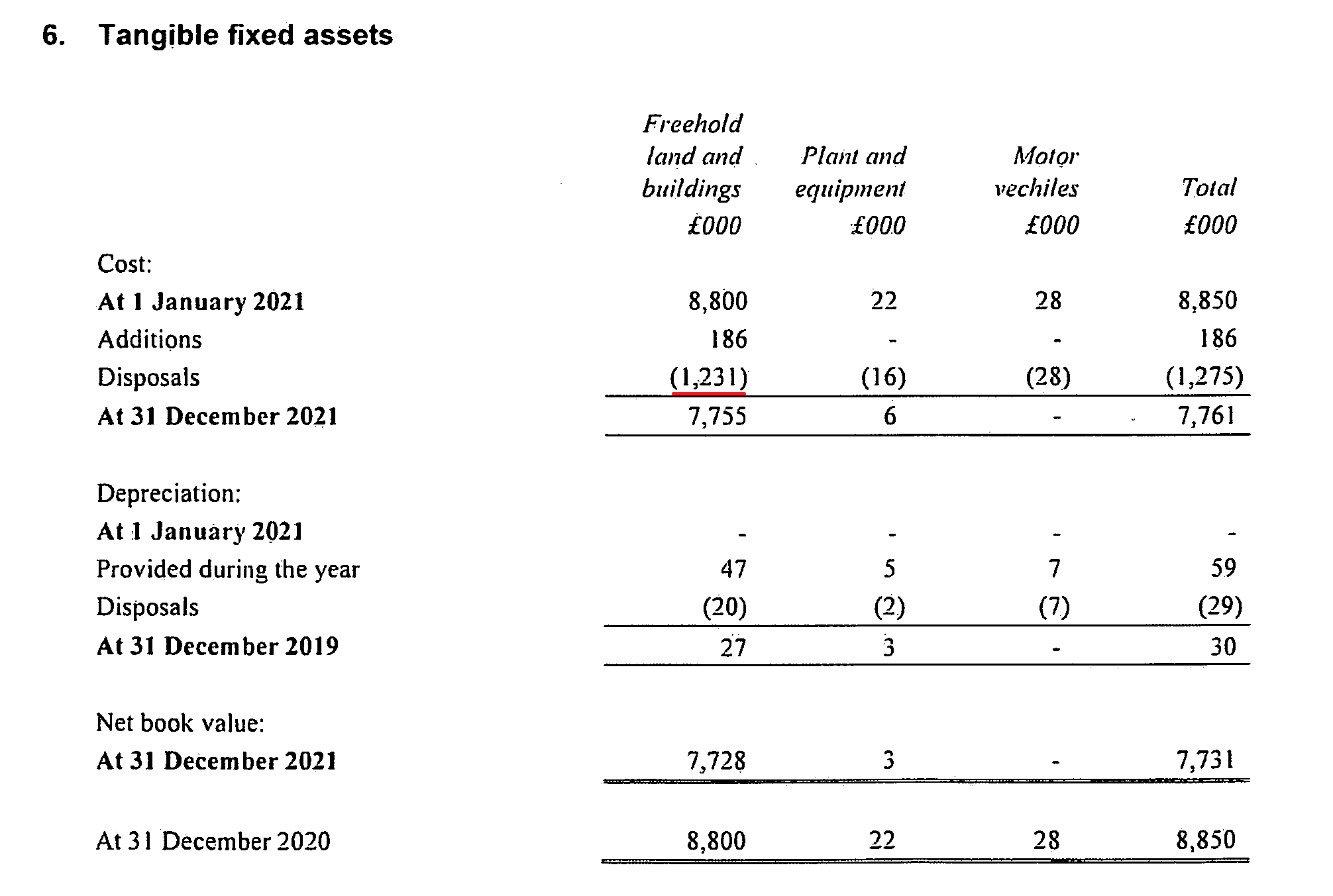

Note too the increase of almost £1m in the amount held as “cash in and and at bank”: this is accounted for by the disposal of some of the assets (property) which BrewDog bought along with the estate:

How much of that cash will now be invested in say bringing deer numbers down on the rest of Kinrara outside of the new fenced area remains to be seen.

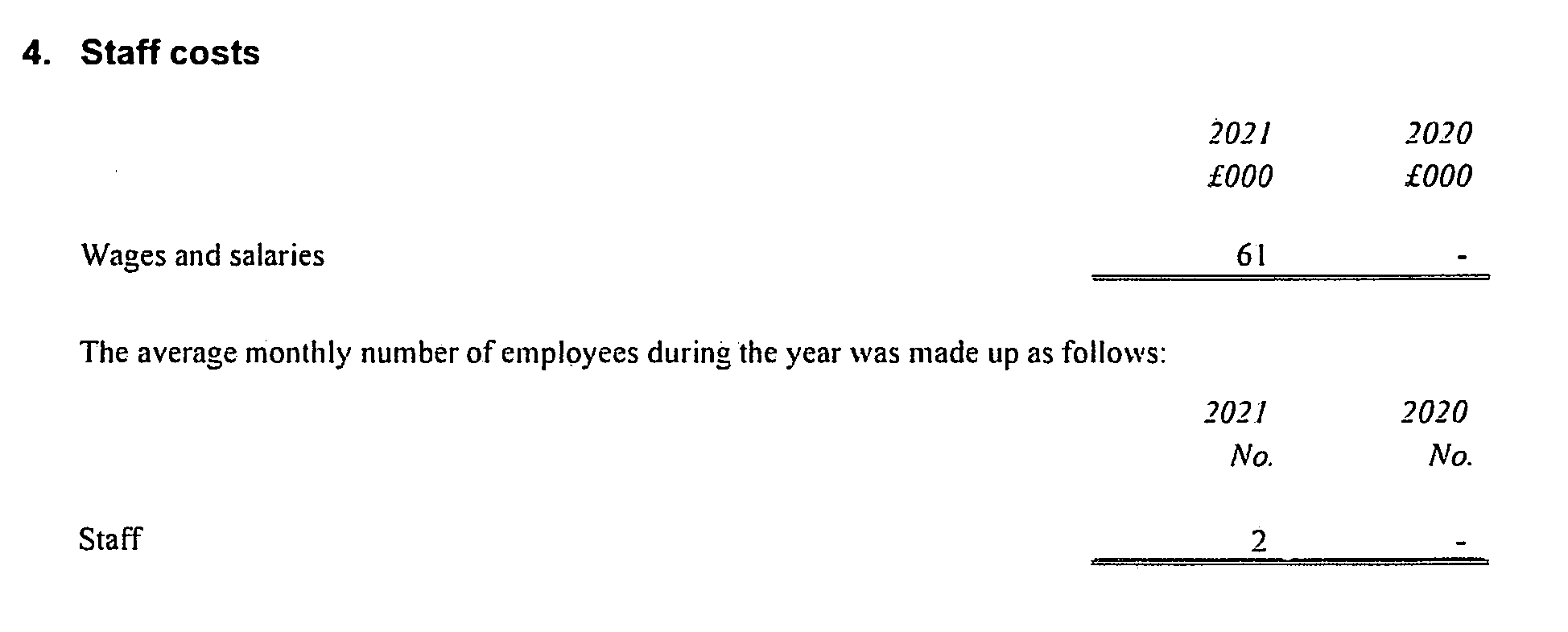

At present, however, instead of employing permanent staff such as stalkers to reduce deer numbers, BrewDog appear to prefer to pay management consultants and contractors who have no permanent stake in how the land is managed. This is causing as much damage as is being restored.

BrewDog’s main accounts claim it is investing money in a range of ground-breaking planet focussed projects including the Lost Forest:

The claim is £15m will be invested in the Lost Forest:

And that BrewDog is taking its responsibilities seriously:

In my view the truth is rather different. As Anne’s photos show this is yet another traditional planting project, with the usual adverse impacts. It has been funded mainly through the public purse with little or no private investment. As for taking a holistic approach, BrewDog has so far avoided saying anything meaningful about what it intends to do to reduce the number of red deer, numbers of which have doubled in Scotland over the last 30 years and are the single greatest reason why woodland and peatland are in such a poor state.

Instead of tackling the real issue, the numbers of red deer, BrewDog’s fencing will direct deer elsewhere, increasing their density per square kilometre and increasing the impact of the natural environment still further.

Far from creating “resilient communities” the Lost Forest has employed just two people. A permanent forester and a team of deer stalking staff would have made a good start but having sold off property, there would now be nowhere for such staff to live. If BrewDog wanted a model for how large landowners might benefit the natural environment and the local community they did not have to look far: Wildland Ltd, who have done so much to enable woodland to regenerate in Glen Feshie, without fencing and created new jobs in the process, bought the big house at Kinrara which now serves as their headquarters.

Source link